What Corporations Know and What They Claim to Know: Eternit and Asbestos Cement Pipes

Stephan Schmidheiny, the owner of fiber cement company Eternit, was convicted of involuntary manslaughter in 2019 for his role in exposing workers to asbestos fibers in Eternit factories. In 2021, he will be up for trial again in Italy--this time for voluntary manslaughter for the deaths of over 300 people caused by indiscriminate exposure to asbestos.

One of Eternit's leading products in the 1970s and 80s was the asbestos cement (A/C) pipe, used widely for roofing and cladding. The document we are highlighting today is an internal Eternit memo from 1982 discussing pushback against Eternit in the Philippines as government officials questioned the safety of asbestos cement pipes.

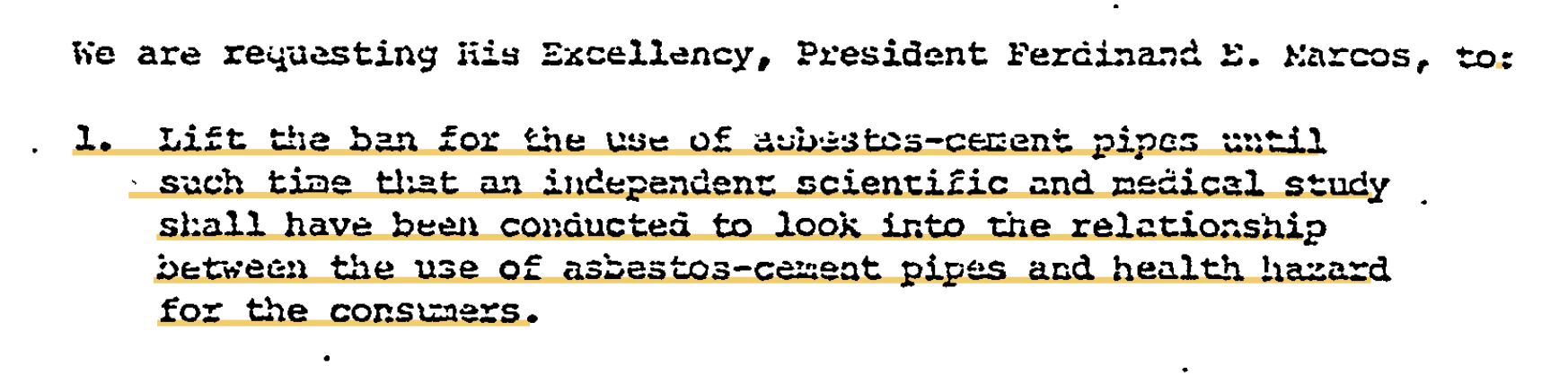

By the 1980s, the toxicity of asbestos had been known for decades and many countries had started to regulate the material. On November 18 1982, the President of the Philippines, Ferdinand Marcos, issued a ban on the use of A/C pipes until an independent scientific study evaluated their toxicity.

In a public statement, Eternit claimed to welcome the study and challenge, insisting they had nothing to hide:

“The asbestos-cement manufacturing industry in the Philippines is happy to hear of the decision of the President to have a committee conduct an inquiry into the relationship between the use of asbestos cement pipes and public health. We have always maintained that an objective, scientific, and medical investigation should be conducted in order to bring out the facts about asbestos-cement pipes.”

In reality, however, Eternit was fighting the investigation of their A/C pipes tooth and nail. In a private letter to President Marcos, Eternit insisted that the ban only be instated if the study proved that the A/C pipes were hazardous.

Eternit's stance--that the ban be initiated only after the study proved a health hazard connection--was in keeping with other toxic industries. Corporations did not want precautionary public health measures, which would require establishing the safety of a product before its use. This would mean that the burden of proof fell on the corporations that claimed the product was harmless.

Instead, industry wanted the burden to be on the state to prove the product dangerous in order to ban it. Corporations, including Eternit's argumentation in this memo, promoted a logical fallacy which equated the absence of the evidence of risk with evidence of the absence of risk.

The most shocking part of the Eternit memo lies in the "Staff Analysis" section. Here, Eternit clearly admits that they were aware of the occupational and public health dangers posed by their A/C pipes:

“Although the situation with the A/C pipe is stabilized, it is likely that occupational exposures to asbestos as well as installation or incidental exposures from A/C sheet or corrugated asbestos in schools, etc. will soon be a matter of concern to the Batasang and Ministry of Health. This probably will not occur until 1983 and hopefully will not impede resolution of the A/C issue. Until the pipe controversy is resolved, Staff recommended that Eternit-Manila not take further steps in encouraging the government to establish occupational standards for asbestos exposure or independent studies of other A/C building products. The current situation is too volatile to interject those potentially inflammatory subjects now” (emphasis added)

Here, one can see the many faces Eternit presented to the public, the government, and internal to the corporation. Examining its different statements, it is clear that despite knowing about the toxicity of its A/C pipes, Eternit continued to push to sell them. The imbalances in the system of accountability and burden of proof only furthered Eternit's efforts to diffuse responsibility. The same mistakes should not be repeated in the 2021 trial of Stephan Schmidheiny; we hope that the courts center public health instead of corporate interests and hold Eternit responsible.